这种事已屡见不鲜:在尝试包装文化遗产的过程中,工艺变成商品、村庄街道变成拥挤的过道,居民则变成卖小玩意的小贩。我们在马六甲鸡场街和会安市河畔观察到这种现象,追求大批量低成本纪念品的逻辑正把原本的手艺人挤向边缘。这不仅是美学上的衰退,也是人口结构上的衰退。在首尔北村韩屋村,保护政策守住了砖瓦屋顶,过度旅游却挤走了近30%居民。长久以来,许多保护政策都受困于“以硬件为先”的短视,只修补立面,却忽视了文化遗产的“软件”:延续生活文化的社会肌理、经济网络和人口稳定性。

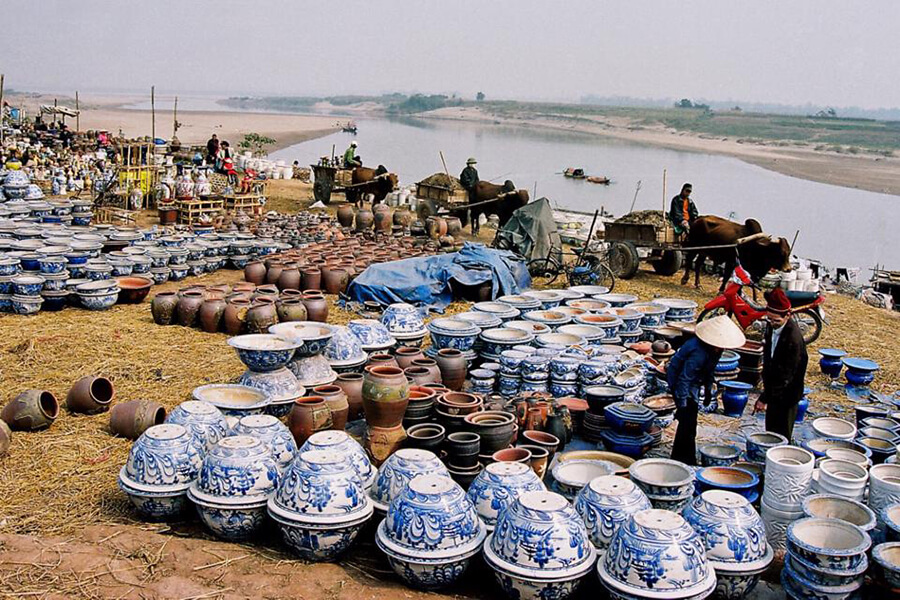

当然,东南亚也不乏先例,试图在展示工艺和把它商品化之间取得平衡。泰国王太后诗丽吉在1976年创立“支持计划”,致力树立全面的典范,在淡季协助农民进入市场,并提供培训和品控,传承制作Mudmee丝绸等传统工艺。另一例子是越南的蝙蝠庄陶瓷村,当地曾组建官方合作社。关键差别在于这些计划绝大多数是从上而下,并依赖大额补贴,是冷战时期的产物。当时,工艺既是文化外交手段,也是一种经济防御。它们的缺点是脆而不坚:只有少数计划能在自由市场中延续下来。在1986年越南提出革新开放后,蝙蝠庄的合作社被家庭工作坊取代。产量有所增长,村庄却变成了标准化大众商品的工业供应链。

由Achariyar “Sai”和Araya “Kruad” Rojanapirom兄妹创立的Kalm Village承袭了这段历史,却一改不能自立的作风。这个工艺综合体由九所建筑组成,围绕两个庭院、家庭咖啡馆、零售店、工作室、画廊,以及展示工艺品制作过程和成品的教室。这里的混合收入结构让商业元素(咖啡馆、商店和场地租用)支援收益较低的“慢文化”业务,例如展览和艺术家驻留项目。这种支援是双向的:以过程为核心的业务为场所注入生命力和特色,吸引寻求较少商品化色彩的游客。这种方式正是利用市场来保护工艺,免受市场影响的典范。

Kalm的介入也提供了信息。每件产品都附有标签,标注制作者、材料与村庄、产地、故事和背景,让交易由不具名的消费变成个人化的赞助。

一如迪恩麦肯奈尔在其1976年的著作《旅游者》中所言,旅游业构建了舞台化的“前台空间”,来满足人们对真实性的渴望。Kalm欣然采纳这个前台空间,却使舞台化的过程变得透明,重新连系游客和后台空间——即手艺人、制作过程和原产地。让这里与众不同的并非纯粹,而是设计。我们无法撇开旅游业,只可精心编排其走向。编排即治理:思考可回馈时间投入和技能的价格信号、可使制作者和产地扬名的信息,以及可防止掠夺性开发的规则。机制至关重要,意图也极其重要。保护政策必须由保护物品转为保护运作系统。如果世界是一个舞台,就让我们来管理它吧。