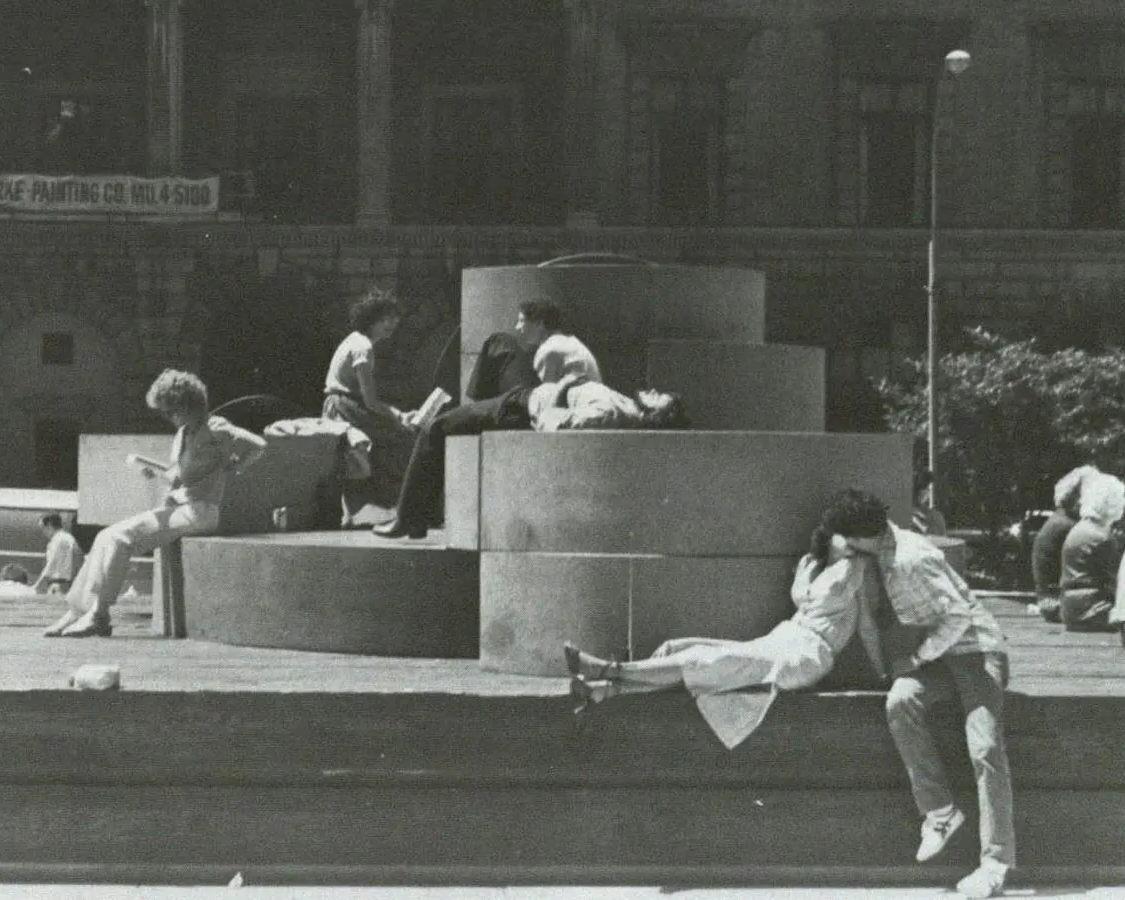

1969年,社会学家威廉怀特在纽约漫步。当时,距离他创造“群体思维”一词已近20年,其影响深远的著作《有组织的人》也出版了13年。一群研究助理手持笔记本、电影摄影机和照相机跟着他走。他们的任务是记录人们实际上如何使用公共空间。

他们的研究结果彻底改变了我们对城市的看法。这个由怀特发起的计划名为“街头生活项目”,为我们现在口中的地方营造开创先河:采用以人为本、协作共创的方法来设计和管理公共空间,使它们变得有活力、舒适与和谐共融。长久以来,人们一直以规范式和从上而下的方式来规划和设计城市,此项目打破了这个局面。时至今日,怀特创建的框架仍然指引着世界各地的建筑师、规划者和社区倡导者。

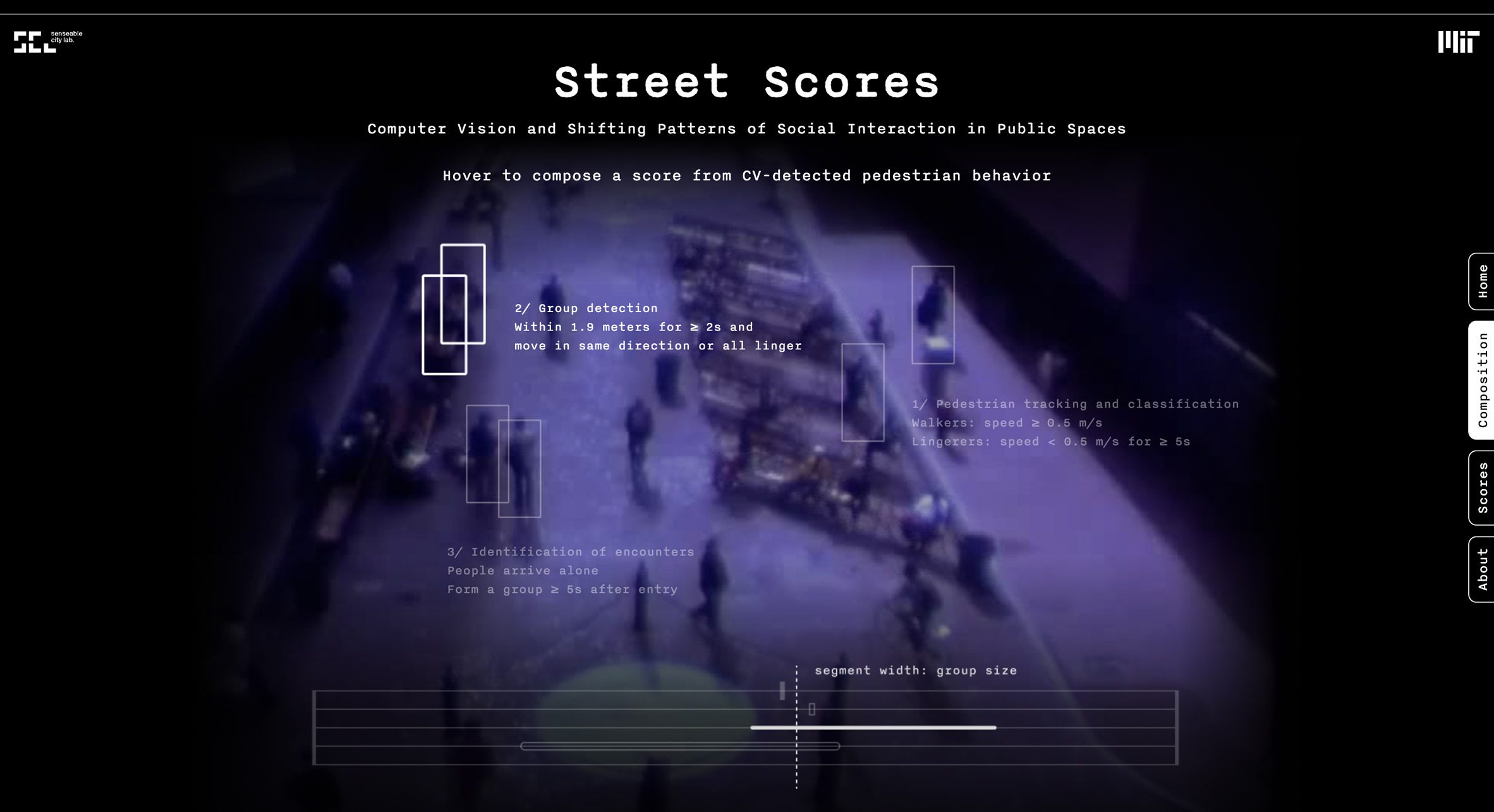

不过,如今出现了一个新的工具:人工智能。如果结合怀特老派的观察技术和人工智能的力量,会发生什么事?建筑师卡洛拉蒂和他的研究团队正是受此启发,在麻省理工学院的可感知城市实验室为怀特的项目设计21世纪的更新版本。

一如拉蒂今年较早时在《卫报》发表的文章所言,通过使用人工智能来分析怀特的历史影像和时下人们使用公共空间的新录像,研究团队发现:“我们交流的性质已然改变”。与50年前相比,人们步行的速度更快,交流则更少。人工智能有助识别这种变化,作为科技乐观主义者,拉蒂认为它或会是一种解决方案。他写道:“如果我们用人工智能来分析户外公共空间,便能为每个公园、广场和街角配备专属的威廉怀特,分别测试改进工程的成效。

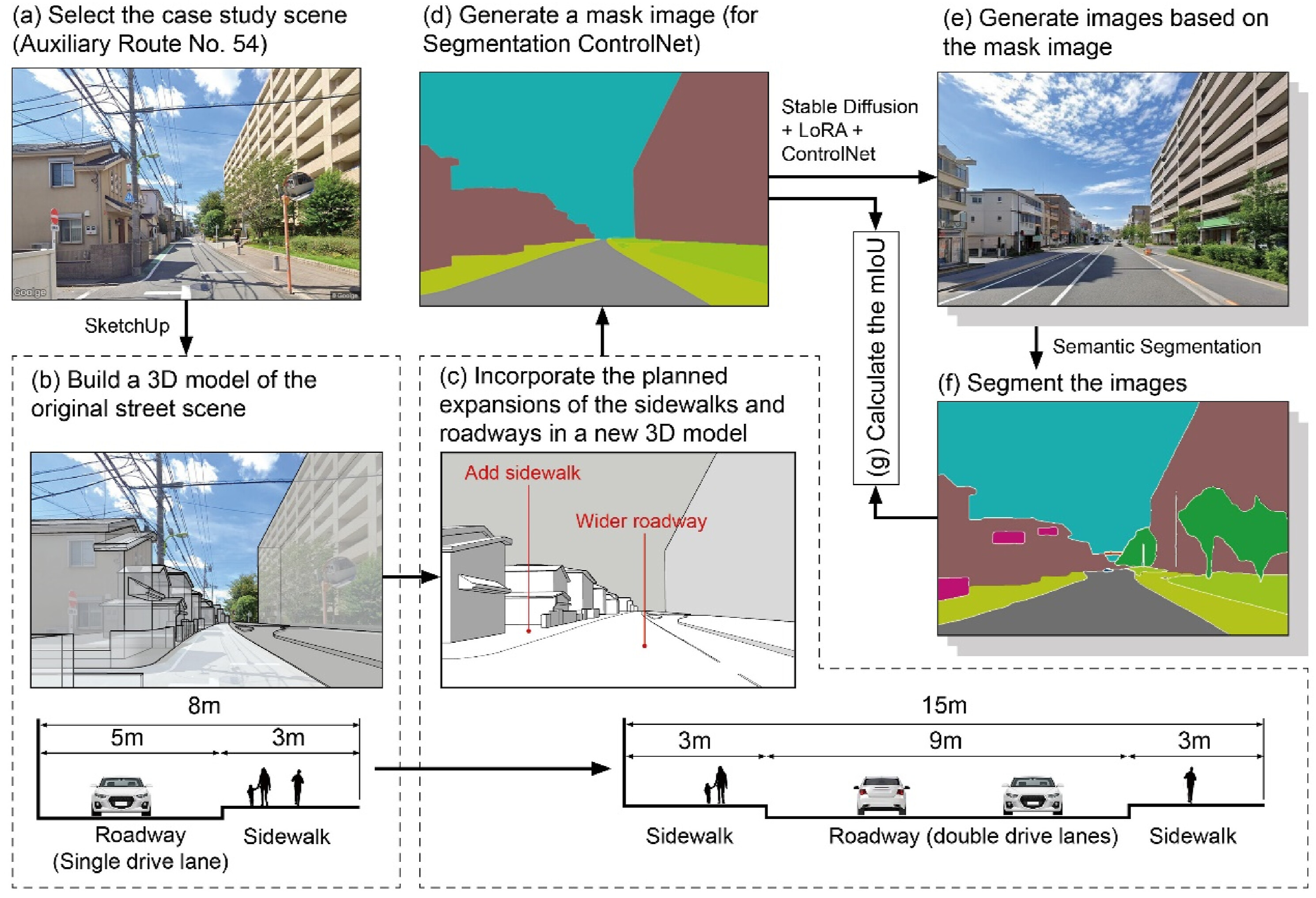

香港和新加坡曾进行类似的项目,研究人员以人工智能分析800个公共开放空间,评估其可达性、便利设施、设计、使用情况和其他方面的品质。调查发现人工智能推荐的方案大致与居民的反馈意见一致,即人工智能分析有望省却大量实地研究的工作。东京曾使用生成式人工智能,协助分析人们如何步行通过不同社区,从而在指定地点可视化呈现和测试人行道工程。赫尔辛基也使用了一个名为“UrbanistAI”的生成式人工智能工具,协助由民间主导的项目重新设计市中心三条街道。

欧华尔顾问有限公司的项目总监刘杰认为这些都是对人工智能的合理应用。他指出:“建筑体现了两个层面:创意构思和严谨执行。后者具有确定性,因此非常适合应用人工智能增强技术。”他补充:“生成式人工智能正于创意领域变得普及,吸引更广泛的群众参与,将带来日益多元化的项目成果。我也预计市场会出现新一代‘前线部署建筑师’。人工智能把这些专业人员从后台工作中解放出来,让他们可专注与客户、终端用户和政策制定者展开有温度的对话。”

刘总监的结语尤为关键:“人情味仍然不可替代”。他表示:“人工智能只是放大了人情味的触达范围和影响力。”事实上,人工智能无法代替政治领导力、设计愿景,以及不同利益相关者之间的协作。即便是广受欢迎的ChatGPT也认同这一点。要求这个生成式人工智能平台阐述人工智能和地方营造议题时,它的结果是:“人工智能为城市设计师提供掌握城市脉搏的新方式。然而,最终仍要由人们来决定他们想要哪一种节奏。”