在世界各地城市,每天都有无数人到海滨河畔一边欣赏景色,一边吃喝玩乐、运动消闲,过形形式式的生活。无论是做什么,能够得享这样的设施,大概未必会多想“优秀滨水空间应具备甚么条件”。

这个问题看似简单,答案却来得复杂。各地城市带来了不少反面例子,让大家汲取前人的教训,常见有兴建大马路、引入公众无法使用的私人海边设施,但原来有些广受赞誉的案例也未达到理想条件。位于温哥华的海堤步道(Seawall)长达22公里,壮丽的自然景观深受民众欢迎,但当地欠缺餐饮娱乐设施经常为人诟病,问题更随着高级住宅开发项目而更趋严重,漫长的步道硬生生变为市郊,气氛异常宁静。 在悉尼,达令港的问题刚好相反,有批评更形容这里是过度商业化的游客陷阱。

新加坡河则找到中庸之道,取得平衡。相比其他城市水道,新加坡河规模较小,以滨海湾为终点,连同亚历山大水道(Alexandra Canal)在内全长不足五公里,却齐集静态消闲设施和精彩夜生活,一幢幢重要地标构成瞩目的风景线,当然还有河水为伴。对于其他有意平衡发展的城市而言,新加坡的成功带来了宝贵经验。

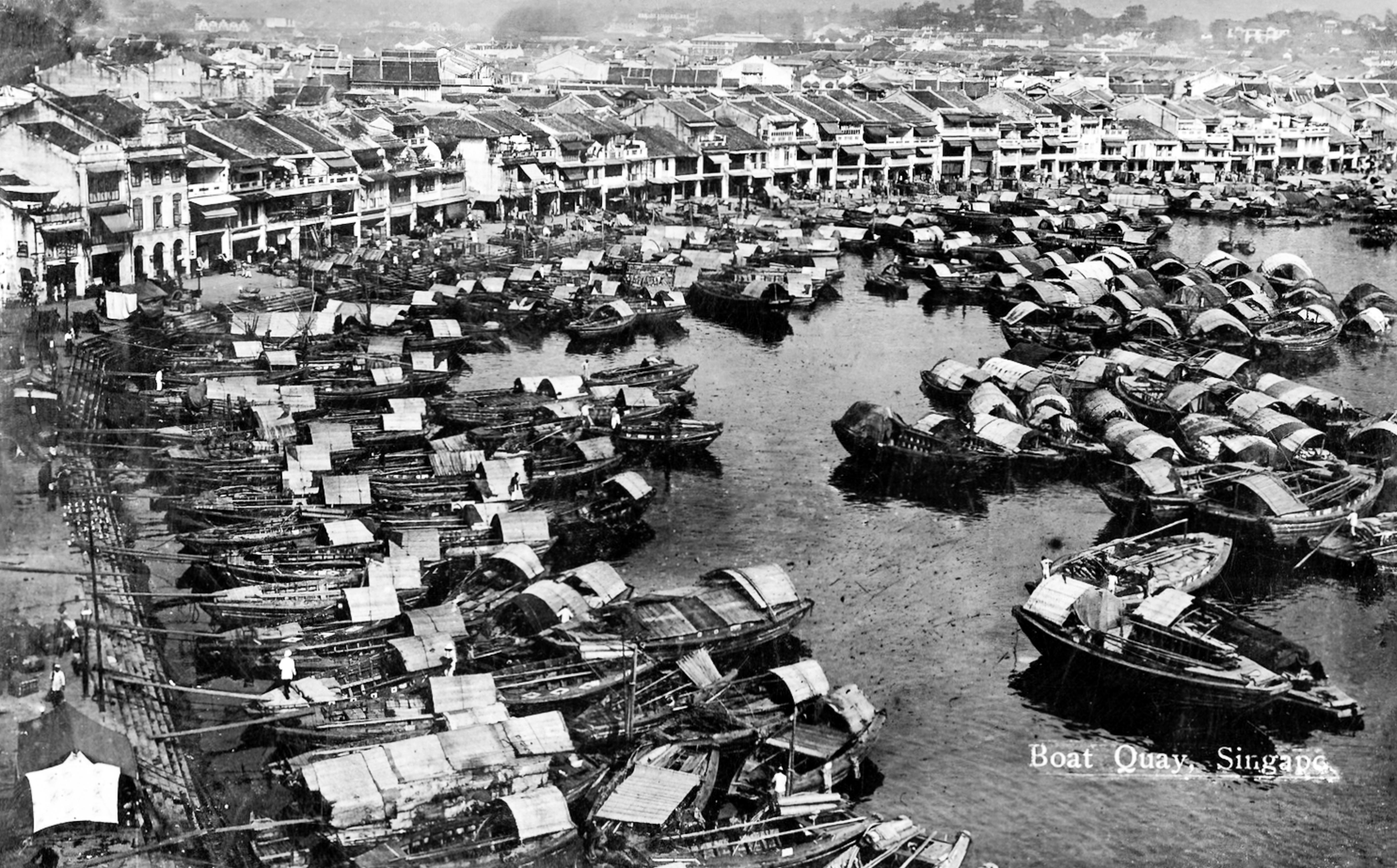

在19世纪,随着新加坡渐渐发展成主要港口,新加坡河成为当地经济命脉,沿岸货仓、店屋林立,主要金融机构和新加坡国会大厦也临河而建。1965年新加坡宣布独立为城邦国家,这时新加坡河因为未受规管的污水长年流入而发出恶臭,促使总理李光耀在1977年提出清理计划。

这项计划带动河流和周边地区逐渐转型。在1989年,当局便刊宪保育驳船码头的108栋店屋,把这些沿岸历史建筑和小尺度街区保留下来。同样别具历史意义的克拉码头位于上游处,也获指定为文物古迹保护区,并于2003年由英国建筑师Will Alsop着手改造成娱乐消闲区域,狭窄步道上一排玩味感重的天幕正是出自他的手笔。

透过这些保育项目,河流和内陆地区的历史连结得以维系,而且有别于其他城市,这里没兴建阻碍通行的高速公路或巨型街区。新加坡国家美术馆、亚洲文明博物馆等主要机构,以至数以千计的办公空间、公寓、酒店、商店和餐厅距离河畔仅几步之遥;前往新加坡河完全不怕路线迂回,沿路走就能抵达。

要实现这样的规划,需讲求各方协调合作。这次也一如新加坡以往的做法,由城市规划机构市区重建局负责提出新加坡河翻新框架作为指引,让发展商开发私营项目,例如克拉码头便是由当地发展商CapitaLand重新发展。

自2012年开始,驳船码头、克拉码头及位于上游的罗伯逊码头便交由非牟利机构新加坡河畔管理协会(Singapore River One,简称SRO)负责管理。罗伯逊码头虽然不算保育范例,但在混合用途发展上成效可鉴。协会的工作主要围绕地方营造计划,其中一项是取消美食热点沙球朥路(Circular Road)的路边停车位,以腾出更多公众共聚空间。协会也在罗伯逊码头增设儿童游乐设施,照顾他们的需要。

新加坡河能够成为人们不假思索便去畅游放松的城市河畔区,取其位置四通八达、体验多元丰富,以及营造了浓厚的地方归属感。归根究底,这几个基本要素往往就是成功规划的关键。