The global pandemic has not only accelerated lifestyle changes that were previously predicted to happen anyway, such as the surge in online shopping, but it has sharpened our focus on conventional shopping malls and their future role in town centres.

In the UK we have witnessed a paradox: the dramatic demise of former retail heavy-weights such as Debenhams and Top Shop driven largely by our online behaviour, which has seen city centre high streets struggling; yet simultaneously, regeneration has become associated with gentrification, a divisive process that often leads to soaring house prices, and displacement of established communities.

Never has sustainable planning and design taken on such significance as now. Yet, the smart city we have been promised has failed to materialise. A smart city should start with a strategy for sustainability and resilience. “We use an evidence-based approach to designing the city,” says Philip Clarke, Project Director at The Oval Partnership, explaining the mechanics of Digital Placemaking (DPM), a pioneering toolkit innovated by the practice to forensically understand what makes a city tick.

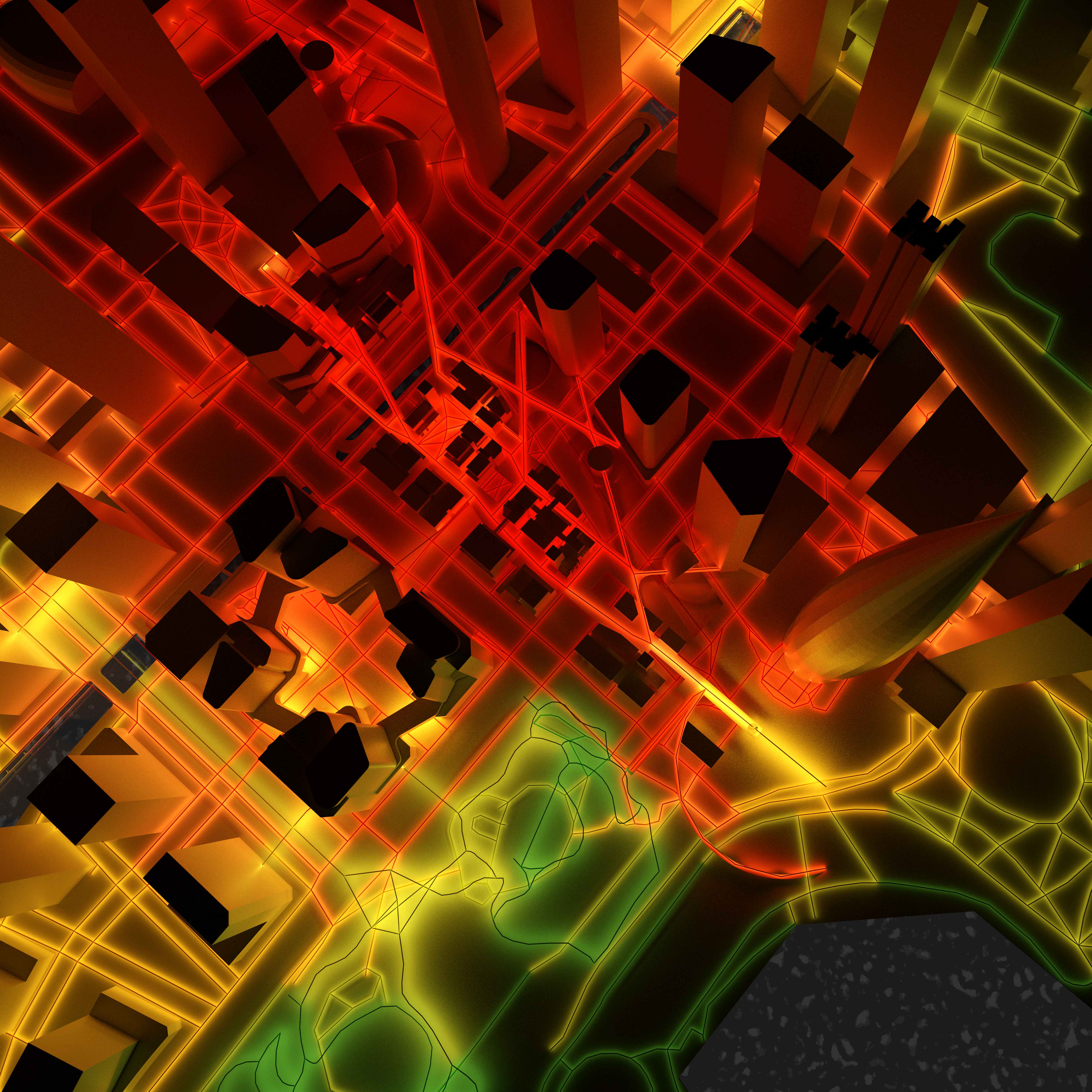

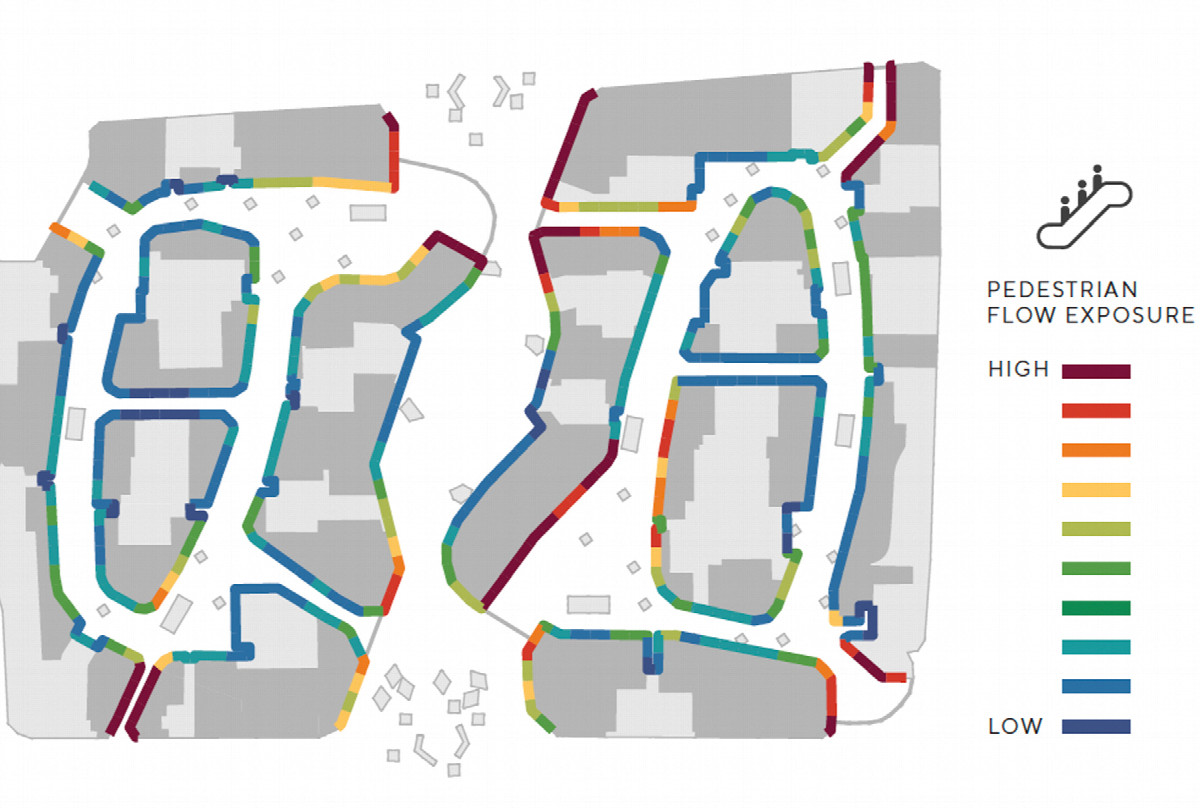

Digital Placemaking feeds into the design process at The Oval Partnership, enabling architects and planners to analyse people movements, detect patterns, assess adaptability, and evaluate designs and built form. “DPM helps create value in the asset enhancement process,” explains Chris Law, The Oval Partnership’s Founding Director, whose appreciation of data analytics was initially fuelled by the practice’s long-standing relationship with a UK-based research team which conducted in-depth studies of mixed-use developments around the world. Unlocking the hidden value of an existing retail centre not only helps rescue it from slow decline, it potentially saves clients the considerable costs of demolishing and rebuilding a more lucrative asset.

However, DPM also makes a significant contribution to sustainability goals. Instead of bulldozing obsolete shopping malls with all the consumption and waste that entails, The Oval Partnership unpicks their locality and gives them a thorough performance appraisal. Very often, these retail megaliths have fallen out of favour with city dwellers yet still have plenty of life left in them. Enhancing the longevity of these buildings through DPM is not about prolonging their useful existence with a lick of paint, but making evidence-based strategic refinements that are bespoke to the socio-spatial and cultural dynamics of the building and its surroundings.

Philip Clarke, leading The Oval Partnership’s urban analytics endeavour, insists that Digital Placemaking allows for a more measured approach to renovation or adaptive re-use. It is not a marketing tool aimed at monetising every millimetre of space in a retail mall—let’s face it, as consumers we are all smarter than that. What it is driven by, is the objective to create great experiences and thus is fundamentally people-centric.

DPM is a sophisticated instrument. It needs to be, as Philip explains, “The idea of separate cellular units in a city for work, retail, leisure, etc is completely outmoded,” he maintains. “In the most successful cities, these worlds are not separate spheres, they are overlapping, multi-faceted, and interconnected.” His job is to understand the underlying structures of a place from a cultural perspective, however these building blocks have had the added hit of being blown apart by the effects of Covid19. “What we are seeing, particularly in traditional retail, is that the standard operating model is no longer fit for purpose,” he argues. “Millennials and Gen Z form an increasingly larger part of the city’s active citizenry and they want experiential, joined-up, connected lives.”

As companies—both large and small—impacted by Covid 19 are pivoting their businesses to meet new cultural agendas, so too are many of the conventional physical constituents of our cities. In a radical departure from tradition for the globally recognised Pritzker Prize, the 2021 award was given to the French duo Lacaton & Vassal. Usually, the prize recognises a practice whose visionary new buildings have achieved new highs in architectural iconography. However, ‘new-build’ does not feature first and foremost in the Lacaton & Vassal stable of projects. Their vocabulary is invariably described by the Award Jury and in the media as restorative and people-centred.

To the clients that The Oval Partnership has developed partnerships with, this will not be an alien phenomenon. In these circles, developers are inclined to consider Asset Enhancement as the new normal for creating value from their estate portfolio. Demolition and re-build, or stripping out a building back to its shell is a last resort. Instead of replacing buildings with yet more unrivalled grand statement-making structures, existing buildings are carefully studied and transformed to redefine their relationship with the public realm, and, more hopefully, actively contribute to it.

The Oval Partnership regenerated a central district in Sanlitun, Beijing by applying an Open City concept whereby success is measured in terms of its effectiveness as a platform for social interaction and the building of social networks. These realms are equally important to the physical surroundings, which are human scaled and create the foundation for continuous and successive adaptation by users. There is ample daylight, strategic views and multi-faceted flexible spaces that might be al-fresco cocktails one season or performing art the next. Over its lifetime, DPM urban analytics have identified changing use patterns that provide vital information to how the neighbourhood might evolve, thus securing the longevity of these buildings and unlocking their potential.

The Sanlitun Taikoo Li project is the paragon for understanding how Digital Placemaking does not end with the re-opening of a carefully adapted and repositioned building redevelopment, it merely transitions into the ”Placekeeping” phase. The Oval Partnership practices regular post-occupation assessments to ensure that the established use-patterns and placemaking narratives they have curated with their clients remain relevant by being given the odd tweak or more.

Of course, not even DPM could foresee the pandemic that led to the sudden collapse of the physical retail market. It has left a post-pandemic China confronting shopping fatigue with a mid-market glut of unpopulated and unloved retail buildings. In order to lure visitors back, developers invariably turn to strategically repositioning their offer. In the past that might have meant cosmetic upgrades to the interior spec and adding a pop-up artisan market. “What is required is no less than breaking up the ‘monoculture’ of the mall to make way for differentiated environments that appeal to an abundant mix of shoppers—both broad and niche.” Phillip explains what this imperative means in practice; “we must create and curate valuable and attractive tenant locations in and around adaptable, credible public spaces for gatherings and events.”

Philip describes how Augmented Reality technology is helping retailers reconstruct some of the social experiences among consumers that have withered and died back from the physical world during the pandemic. “By seeding trans-media narratives that offer shared and shareable interactive experiences, we curate a setting for emergent forms of playful urban interaction that is in such demand,” he continues, describing how to harness grass-roots urban participatory practice to generate ideas and engender stakeholder ownership.

In the UK, the pandemic has shone a brighter light on what was already happening ‘on the High Street’: over-reliance on traditional retail presaging their slow and painful decline. The pandemic accelerated this process and as Philip observes both in Asia and Europe, “What used to be an industry led by experience and instinct,” nurtured by cyclical real-estate trends of boom and bust “is giving way to a much more evidence-based and location-specific analysis providing an informed view of a place to chart its fortune in a changing market.” Trusting old instincts about property and place won’t wash as the pandemic threw such a huge spanner in the works, he reasons. What we need for the revitalisation of city centres is to embrace a new narrative, one that is led by community, culture and connectivity.