Image By: TZIDO SUN

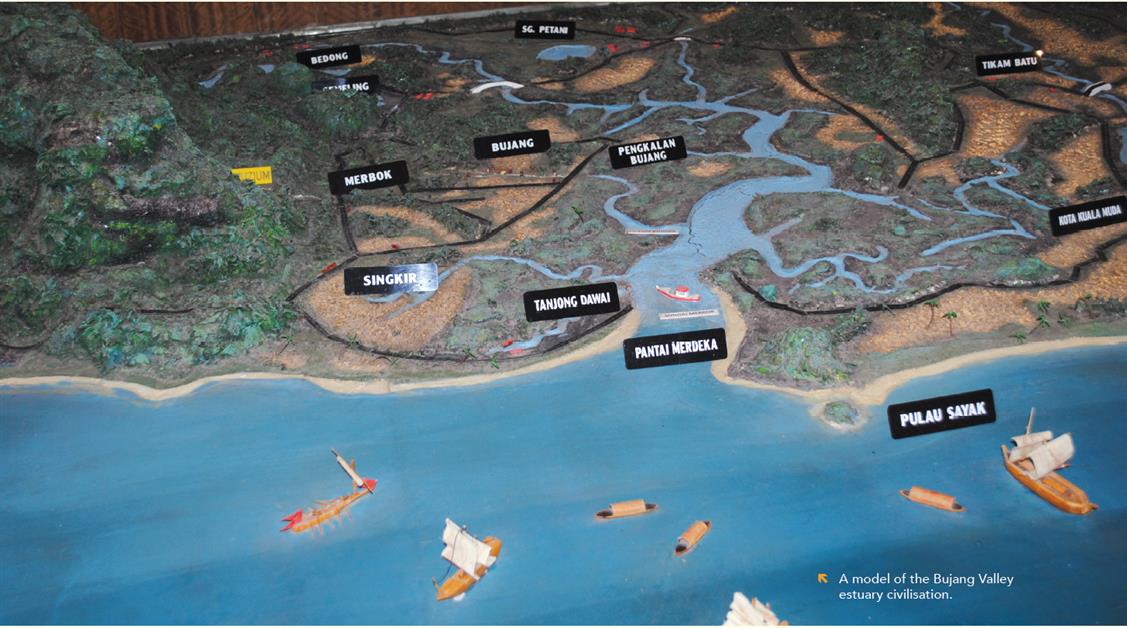

Trade has long been Southeast Asia’s quiet architect. From Singapore’s rise as a British colonial port to Kuala Lumpur’s transformation from a muddy riverside village into a commercial hub tethered to Port Klang, the region’s cities were seeded by commerce. Even earlier, the Bujang Valley in northern Malaysia served as a maritime entrepôt connected to Indian Ocean trade. In Thailand, Ban Chiang pottery villages show that craft production and exchange routes were thriving centuries before modern cities took shape. The kampong was often the first spark of urban life.

Kampongs are not just sites of underdevelopment awaiting modernisation; they are nodes of social and economic vitality. Their evolution is often driven by a rootedness in place, relationships and material — kinship, craft, trade — not by formal masterplans. While modernist planning tends to impose grids, towers and highways, kampongs offer a different kind of urbanism: adaptive, human-scaled and anchored in cottage production. Rather than displace them, urban planners would do well to support kampongs — by protecting local industries, improving access without disruption and integrating their economic role into broader urban systems.

One example of less-desirable planning is Kuala Lumpur’s Kampung Baru, one of the city’s last remaining urban villages, which has faced repeated redevelopment proposals that risk displacing residents in favour of high-rise projects, despite its central location and rich cultural history. In contrast, Yogyakarta’s Code River kampongs were revitalised through a community-led design initiative in the 1980s by self-taught architect YB Mangunwijaya, demonstrating how bottom-up planning can enhance both quality of life and community resilience.

The nature of trade itself is also changing. Where the 20th century favoured consolidation and scale — container ports, industrial parks and centralised logistics — the 21st century is decentralising. New technologies allow kampongs to reinsert themselves into global supply chains on their own terms. In Vietnam, the bamboo and lacquerware villages of Bat Trang and Phu Vinh now reach customers via Instagram and TikTok Shop. In Indonesia, Pekalongan’s batik artisans have moved beyond tourist markets, collaborating with fashion brands and textile buyers abroad, supported by digital payments, fulfilment platforms and shared logistics. In the Philippines, piña and abaca weavers in Aklan and Iloilo are now part of sustainable textile networks that feed into eco-conscious fashion brands across the Asia-Pacific. In Malaysia, rural mat weavers have begun working with urban intermediaries to fulfil custom orders and pop-up demand in city-based artisanal markets. Still more craftspeople across the region, from Indonesia to Taiwan to Tibet, collaborate with designers from their own countries and abroad to develop markets and preserve crafts.

These are no longer isolated producers shipping wares to a city bazaar — they are nodes in a complex ecosystem of production, branding, logistics and marketing. While their scale may be small, their participation is meaningful: rural producers are embedding themselves into cross-border commerce, often through partnerships with NGOs, e-commerce platforms, diaspora intermediaries or creative brands. Such embeddedness gives kampongs not just economic relevance but strategic value: they offer distributed production capacity, cultural specificity and resilience — assets that are increasingly prized in an era of supply chain shocks and demand for ethical sourcing.

Kampongs remain trading places — only the medium has changed. As Southeast Asia’s cities continue to grow, the challenge is not to build over kampongs, but to build with them. They offer a vision of development that is rooted, distributed and deeply Southeast Asian.